Dear Friends,

For Ambiguous Zones 11, we are pleased to introduce guest author Keenan Jay, who wrote an insightful essay on Arakawa’s solo exhibition of mainly coffin works at the Zuni Gallery in Buffalo, NY, in March of 1964. Jay is a researcher of modern and contemporary art with an interest in diasporic art and the neo-avant-garde. He was a 2021 research fellow with PoNJA-GenKon and Asia Art Archive in America and has recently presented at the annual conference of the Association for Asian American Studies among others. He has been conducting a series of oral history interviews on Montez Press Radio since 2019.

Yours in the reversible destiny mode,

Reversible Destiny Foundation and ARAKAWA+GINS Tokyo Office

In a January 1967 Artforum article, critic Yoshiaki Tono recalls his surprise at a new group of artists who had appeared in Tokyo during the late 1950s. He frames these artists, who called their collective Neo Dada (initially the Neo Dadaism Organizers), through their formative postwar upbringing, writing that “they desired an art which could respond more directly . . . to the chaotic realities of the world they knew.”[1] This world was that of Japan during reconstruction, a world trying to come to terms with its wartime imperialism against a backdrop of leveled cities and widespread famine. More recently, it was the world of the ensuing development and consumerism that had turned “the teeming city of Tokyo” into an “immense junk-yard”[2] and of the Anpo treaty’s re-signing, which would establish Japan’s Cold War role despite popular protests against it. Given that the works of Neo Dada were inextricable from these circumstances, Tono argued that the group’s activities should be understood primarily in sociological rather than artistic terms.

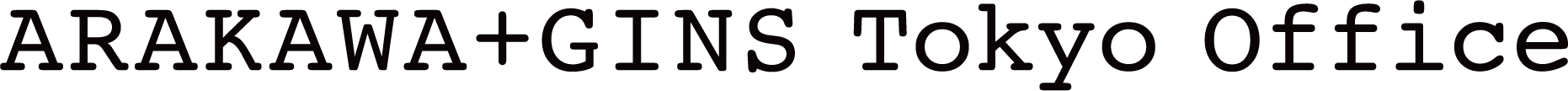

Having introduced Arakawa in this way, Tono goes on to observe in the artist’s work an “obsession with death and nothingness,” reflecting the sensibilities of the “post-Hiroshima generation.”[3] Tono felt this was particularly true of Arakawa’s coffin-like sculptures. Perhaps Arakawa’s best-known works outside of his diagrammatic paintings and architectural projects with Madeline Gins, these ominous boxes confronted the viewer with dimensions suggestive of human proportions. The works required the viewer to remove the lids to reveal the biomorphic and mutant masses contained inside (fig. 1). Made primarily of cement and cotton, Arakawa also sometimes embedded objects from Tokyo’s industrial refuse into his compositions. However, he typically used such discarded objects sparingly, turning their original use-values alien through their isolated appropriation.

In this same article, Tono moves on to a discussion of Arakawa’s immigration to New York in 1961 and, jumping to 1963, his abandonment of the coffin works in favor of the diagrammatic paintings for which he would become known. 1963 saw Arakawa’s first Galerie Schmela exhibition in Düsseldorf and the beginning of his collaboration with Madeline Gins on The Mechanism of Meaning, with his work at this time employing diagrammatic and informational visual languages that marked a definitive departure from his sculptural practice. By Tono’s condensed account, it would indeed seem that “Arakawa left his boxes in Japan.”[4]

In the period immediately following Arakawa’s move to New York, however, he not only continued to produce new coffin works but also substantially developed their concept and form. In March of 1964, an exhibition at Zuni Gallery in Buffalo, NY, showcases the culmination of this brief but compelling period (figs. 2-5). At first glance, the works in the show are familiar: the coffin-like sculptures that gained Arakawa notoriety in Tokyo populate the space, punctuated by diagrammatic drawings that evoke his painterly output in New York. Yet we soon notice a difference in these coffin works, with their unusual mechanical parts conjuring the image of reanimation rather than the mortuary air of their predecessors. The Zuni exhibition therefore reveals a distinct period within an already established body of coffin works that has gone relatively unstudied, marked by an increased complexity and modification via mechanical apparatuses.

An unpretentious gallery in a basement in Buffalo, New York, artists Ben Perrone and Adele Cohen started Zuni in 1963 and operated it for two years. Arakawa’s show had been coordinated in early 1964 by Bill Dorr, whom Perrone described to the Reversible Destiny Foundation as “somewhat of an entrepreneur in the arts.”[5] Dorr also helped organize a group exhibition a few months prior to Arakawa’s solo show, featuring Arakawa, Ay-O, Masunobu Yoshimura (another central Neo Dada artist), Robert Morris, Dorr himself, and other artists including John Chamberlain, Robert Motherwell, Claes Oldenberg, and Jim Dine (fig. 6).[6] The first four of these artists had in fact shown together in a separate group exhibition almost a year earlier entitled Boxing Match at Gordon’s Fifth Avenue Gallery in New York City, suggesting a relationship between Dorr and the gallery.

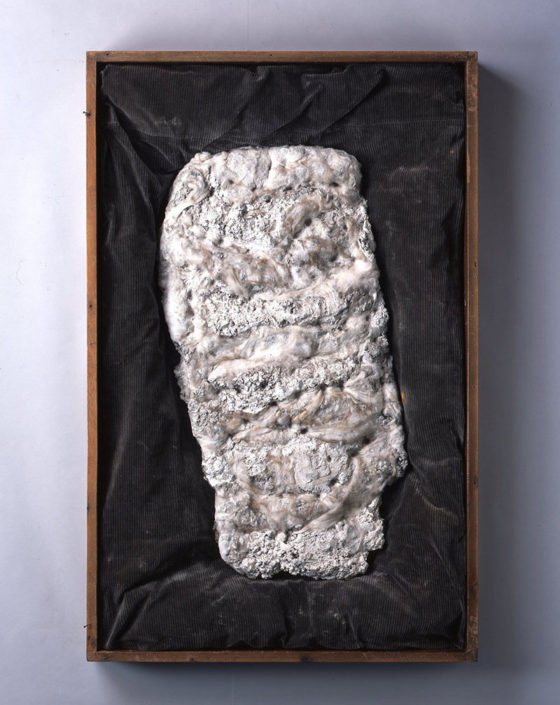

The Zuni solo exhibition of 1964, nearly one year after the Boxing Match show, confirms such a trend through a new set of coffin works.[12] These works contain long glass tubular rods arranged in organized rows, compartmentalized plexiglass structures, and an abundance of wires, switches, buzzers, and hinges (fig. 9). In general, the Zuni works are distinct in their language of technological complexity uncharacteristic of the coffin works prior to Arakawa’s move to the United States. One such work, simply titled Work (1963), makes apparent the extent to which the industrial parts Arakawa utilized no longer adorn the corporeal masses and instead have become incorporated in ways that imply elaborate functions (fig. 10a).[13] This large coffin work holds within its complex apparatus a smaller one, as if expropriating a vital resource from it. In this remarkable instance of self-referentiality, the smaller coffin—reminiscent of the earlier and more simple coffin works—is hooked up to a series of conduits and wires housed in different interconnected compartments. A cord spills out from the frame of the larger coffin, connecting it to a bulbous glass fixture suspended above a small vitrine resting on the floor. This work also appears in color in a January 1964 issue of Mizue magazine, showing a central object on its bed of lilac satin in the smaller coffin, which itself is nested on a lilac bed within the body of the larger coffin, producing a humorous mise en abyme effect (fig. 10b).

Arakawa’s drawings exhibited in the Zuni show also seem to be in a state of transition, en route to the diagrams of his mid-career work. While these works employ the visual language familiar from the later paintings, they also feature more organic, growth-like forms and painting methods not characteristic of them. Arakawa’s choice of watercolor, whose transparent wash preserves the presence of hand, heightens this effect as the brushwork does not yet display the removal of his touch seen in the later paintings. Accordingly, these works may be seen to link the corporeality of the coffin works and the diagrammatic language of the paintings to follow (fig. 11).

In this simultaneous mechanization of the coffin works and atypical biomorphism of the diagrams, we observe Arakawa thinking through new artistic ideas in his existing practice. A significant factor in this development was Arakawa’s relationship with Duchamp, which began in 1961. According to an oral history interview with Arakawa conducted by Reiko Tomii and Midori Yoshimoto, Arakawa met Duchamp immediately upon his arrival in New York.[14] The two maintained a friendship until Duchamp’s death in 1968 and his influence would have profound consequences on Arakawa’s practice.

The fact that Arakawa made reference to the older artist in his later coffin works indicates this. For example, Arakawa’s use of both positive and negative casts of body parts in these late coffin works recalls Duchamp’s own casts in With my tongue in my cheek (1959) and his “erotic objects.” We also observe references in Arakawa’s titling, such as The Method of Advancing a Great Distance by Descending, which directly alludes to Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2, (1912). Although this coffin sculpture was not shown at Zuni, likely due to the work’s inclusion by John Weber in the Dwan Gallery’s own box-themed show that took place around the same time, another smaller, unidentified Zuni work shares many of its distinctive features. These include its mouse-eared silhouette and the body’s framing of a gridded, topological plane akin to the Euclidean space of the diagrammatic drawings (fig. 12). Such recurring features suggest that this smaller work might have served as a study or model for The Method of Advancing a Great Distance by Descending. This association helps to contextualize the series of square doors set into the base of the smaller Zuni work, a feature that also appears in Arakawa’s Diagram with Duchamp’s Glass as a Minor Detail (1964). This latter sculpture, which was not a coffin work, paid homage to The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-1923), also known as The Large Glass.

Instances such as these in the later coffin works underscore the importance of Duchamp in their new integration of complex machinery. As the coffin works became more cyborgic, they also entered into close dialogue with the bachelor machines of The Large Glass. Both reimagined the figure through a mechanics of absurd expenditure: like the bachelor machines’ fruitless endeavoring, the late coffin works labor futilely. These parallels suggest that Duchamp played at least some role in the mutation of Arakawa’s sculptural practice after his arrival in New York.

Arakawa’s next exhibition, Die-agrams, marked his divergence away from the coffin sculpture format while maintaining a connection to his fascination with death in the next major period of his oeuvre. A further ode to Duchamp with its use of pun, this inaugural solo exhibition at the Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles, opened on March 29th of 1964, less than a week after the Zuni exhibition closed. It seems, then, that it would be more accurate to say that Arakawa left his boxes in Buffalo than in Japan as suggested in the article by Tono cited at the beginning of this essay, a misunderstanding further perpetuated by Arakawa’s omission of the Zuni solo from his exhibition record altogether by the time of his show at the Stedelijk van Abbemuseum in December 1966. His reasons for this were never stated, though it suggests that he no longer saw the exhibition and its works as representative of his artistic identity. Analysis of the late coffins works, therefore, has much to tell us about Arakawa’s thinking at this crucial juncture in the trajectory of his career. Further study would not only yield new insight into these relatively obscure works, but also into Arakawa’s own self-conception as an artist within the social context he encountered in New York.

[1] Yoshiaki Tono, “Shusaku Arakawa, Tomio Miki, and Tetsumi Kudo,” Artforum (January 1967): 53.

[2] Tono, “Shusaku Arakawa,” 53.

[3] Tono, “Shusaku Arakawa,” 53.

[4] Tono, “Shusaku Arakawa,” 55.

[5] Email correspondence between Ben Perrone and Amara Magloughlin, June 9th, 2018.

[6] These latter artists appear to have come from Dorr’s own collection. Email correspondence between Ben Perrone and Amara Magloughlin, June 9th, 2018.

[7] This exhibition was revisited by Castelli Gallery in 2019. The exhibition catalog includes materials crucial to this research and may be accessed at https://www.castelligallery.com/publications/1963-boxing-match-revisited.

[8] Donald Judd, “Reviews for Arts Magazine, April – May/June 1963,” in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959-1975: Gallery Reviews, Book Reviews, Articles, Letters to the Editor, Reports, Statements, Complaints (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975), 90.

[9] ARTnews reviewer K.L. writes that “Cloud, a horizontal box (a grey plane) suspended at eye level, gives a curious effect of blindness.” K.L., “Boxing Match,” ARTnews (March 1963): n.p. Re-printed in Boxing Match: 4 Sculptors: Arakawa, Ay-O, Morris, Yoshimura, ed. Castelli Gallery (New York, NY: Castelli Gallery, 2019): 24.

[10] Judd, “Reviews,” 90.

[11] Yusuke Nakahara, “Shusaku Arakawa,” Bijutsu Techo (October 1963): n.p.

[12] The possible exception of Be Kind Enough to Turn the Switch On is mentioned above.

[13] Yoshiaki Tono, “Statement by Japanese Vanguard Artists from Saito to Arakawa,” Mizue (January 1964): 26.

[14] Oral History Interview with Shusaku Arakawa, conducted by Midori Yoshimoto and Reiko Tomii, April 4, 2009, Oral History Archives of Japanese Art (URL: https://oralarthistory.org/