Front cover of Madeline Gins’s Heren Kerā matawa Arakawa Shūsaku (Helen Keller or Arakawa).

Translated by Momoko Watanabe. Tokyo: Shinshokan, 2010.

In honor of Blindness Awareness Month, Distraction Series 12 focusses on Madeline Gins’s book Helen Keller or Arakawa (1994) and the influence that Helen Keller had on Arakawa and Gins’s architectural practice. While Helen Keller is an extremely well-known figure in both the United States and Japan, Gins’s in-depth meditation on Keller’s thought and experience goes well beyond the usual elementary school focus on Keller’s childhood and tutelage under Annie Sullivan. Gins incorporates direct quotes from Keller along with poetic imaginings of her experience of being both blind and deaf and employs these against a backdrop of Arakawa’s paintings in particular to probe the ways in which we experience the world as well as what it means to inhabit an architectural body.

Her Socialist Smile (2020), a new documentary film on Helen Keller by filmmaker John Gianvito, was available to stream last week as part of the New York Film Festival. With its focus on Helen Keller’s political activism, it highlights Keller as an historical figure who is still very relevant, something Arakawa and Gins felt deeply. From the festival:

“In his new film, Gianvito meditates on a particular moment in early 20th-century history: when Helen Keller began speaking out passionately on behalf of progressive causes. Beginning in 1913, when, at age 32, Keller gave her first public talk before a general audience, Her Socialist Smile is constructed of onscreen text taken from Keller’s speeches, impressionistic images of nature, and newly recorded voiceover by poet Carolyn Forché. The film is a rousing reminder that Keller’s undaunted activism for labor rights, pacifism, and women’s suffrage was philosophically inseparable from her battles for the rights of the disabled.” (https://www.filmlinc.org/nyff2020/films/her-socialist-smile/)

The film is no longer streaming, but we will send a follow-up message once it becomes available to rent.

We hope you enjoy this month’s newsletter and will be in your inbox again on November 6th – the day before Madeline’s birthday – at the end of what is sure to be a very important week.

Yours in the reversible destiny mode,

Reversible Destiny Foundation and ARAKAWA+GINS Tokyo Office

On Helen Keller or Arakawa

Yamaguchi, Masashige. Kodomo no denki zenshū 3: Heren Kerā

[Collected biographies for children 3: Helen Keller], Tokyo: Popura-sha, 1968.

Helen Keller (1880-1968), who became blind and deaf at a very young age, is an extremely well-known figure in the U.S. for her considerable achievements as an activist and advocate on behalf of those with disabilities. Many of us first became acquainted with Keller through a book in elementary school, and, as an adult, Madeline Gins practiced her Japanese by reading an equivalent book included in the Japanese curriculum, writing notes to herself in the margin. Helen Keller was a huge source of inspiration for both Gins and Arakawa, which is especially apparent in their architectural projects. In the mid-1990s, Gins wrote a work of ‘speculative fiction’ entitled Helen Keller or Arakawa (1994).

In this book, Gins weaves together (or ‘cleaves’) quotes and anecdotes from Keller into a narrative that is equally her own and Arakawa’s, one in which Keller’s lack of vision and hearing becomes the ‘blank’ evoked in both Arakawa’s artwork and the pair’s own philosophical praxis. From the very first sentence, Gins communicates to the reader that we are in an experimental world that will follow rules to which we may not be accustomed. In this experiment, she elides the persons of Helen Keller, Arakawa, and herself into an overarching sense of ‘I’ that encompasses these three beings. Throughout the entirety of the book, it is not always clear which of the three is expressing a story or memory at any given moment and this primes the reader to be prepared and more accepting of yet another elision – in this case, between a person and their environment (or ‘surround’ to use Madeline and Arakawa’s term) into an ‘architectural body’, or a ‘puzzle creature’, or an ‘organism that persons’.

Gins makes use of a number of Helen Keller anecdotes that could each be read as a detailed ekphrasis of a painting by Arakawa. This coalescence of thought opens up further avenues of investigation into the philosophy and architectural practice of Gins and Arakawa. Despite the main intent of the book, it has the extra value of offering a very cogent interpretation of Arakawa’s body of work.

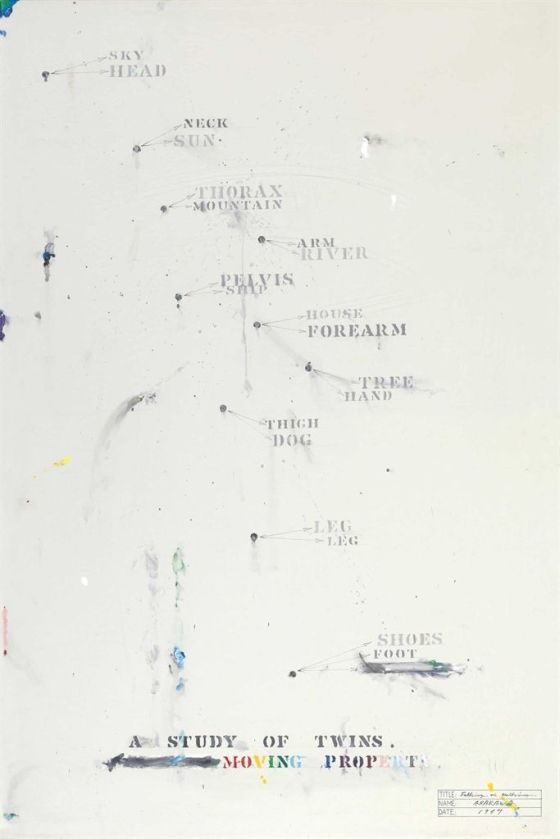

Montage – Helen Keller standing on one of the floor panels of The Process in Question, 1987-99

Arakawa, Diagram of Part of Imagination, 1965

A jazz musician, in one story told from Arakawa’s perspective, asked for a portrait of herself and was disappointed with the result. Arakawa had “found” her, and therefore sketched her, in all corners of the room, showing the conceptual beginnings of the architectural body. The room became the frame and everything within was the portrait. This mode of configuring space reminded Arakawa of a blueprint, and in this format, he recognized the way in which his imagination was ordered. For him, it made complete sense to stage or frame identity in this same way. Taken as a ready-made, he saw each blueprint as a “perfect example of the condensed perception of the other.” Diagram of Part of Imagination (1965) is an example of a painting resulting from this line of thought, consisting of a diagram of a living space with each room or area labeled. Dots and lines become loaded symbols that delineate space or situate things within space, but they also embody time and movement across spacetime. At the same time, as the title suggests, what is missing from the canvas is equally present. Part of the imagination is focused on or within this room, but the rest of it is “busy with a great number of other things and events.”

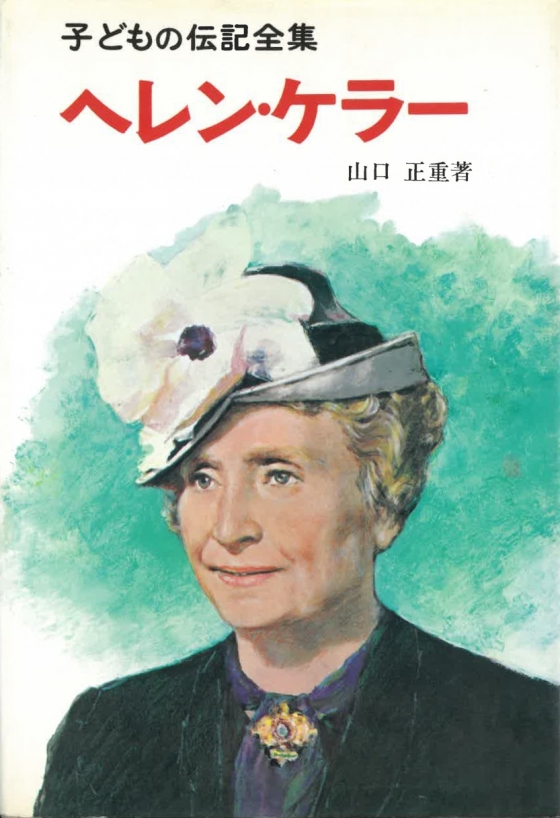

Arakawa, Talking and Walking, 1969

In Talking or Walking (1969) we find dots breaking the body into parts that are then correlated with things found in the environment, further ordering space. The body is clearly in motion as you can see from the specific position of the dots representing arm, forearm, hand, and foot, given their progression, forward in space, from the head. As Gins quotes Karl Marx: “We have sufficiently explained the world, the point is to transform it.” Gins goes so far as to interpret Marx’s ‘point’ as an object, conflating this point with the symbol Arakawa utilized to great effect in his work, and then personifying it as a being named Voluntar. As Voluntar, the dot becomes the “darling of place markers of plasticity, limning character and will.” While Voluntar marks where something is in a given moment, she also represents all potential movements and transformations, which imbues each dot with all the weight of an ‘organism that persons’, as it is always on the verge of initiating any of an infinite number of potential actions. These potentialities can all be understood to be present in Arakawa’s paintings.

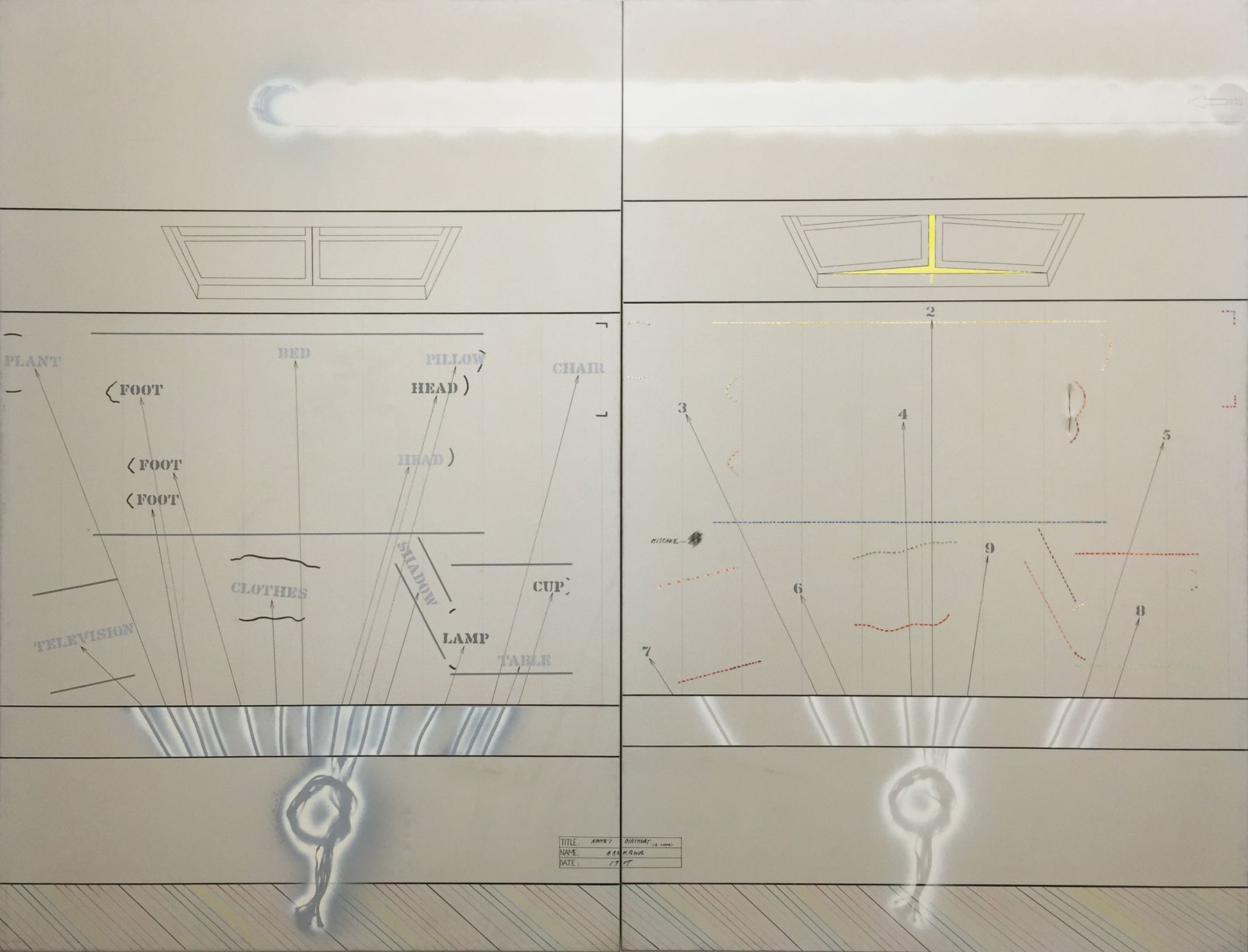

From the perspective of Helen Keller, Gins relates a variety of experiences including an anecdote in which rope was used to demarcate an area outdoors, where Keller could then run freely. Gins imagines that Keller must think in diagrammatic terms in order to situate herself in space so that she can move within and between rooms, much like the mapped space of an Arakawa painting. Through another foray into Keller’s lived world, Gins forges a connection between her sense of light – something Keller dreamed of – and Arakawa’s employment of it, in part as something that helps give character to a window and also as something that can fill a space. Keller went through a phase in which she loved to count things, and Annie Sullivan, her teacher, feared she might get the idea to count the hairs on her own head. Arakawa’s painting, Name’s Birthday (1967), brings all of these themes together. A few horizontal lines denote walls, diagrammatic space, as well as the boundaries of objects that are labeled with their names on one half of the painting and numbers corresponding to seemingly different things on the other. Whether these numbers refer to different objects or simply indicate that the objects have moved is open to interpretation. The lines on the right side are broken up into dots. Faint vertical lines further divide the space. Arrows pointing to each word and number stem from a knotted rope, perhaps indicating the connection between these objects, all parts of a whole, unified in a single organism. One open window at the top on the right side allows the light into the room to become almost another object in and of itself. The evidence of this light is really only found around the string and rope, which serve as placeholders for a composite being, and here, to use Gins’s phrase again, we find that the light is “limning character and will” in a more literal way.

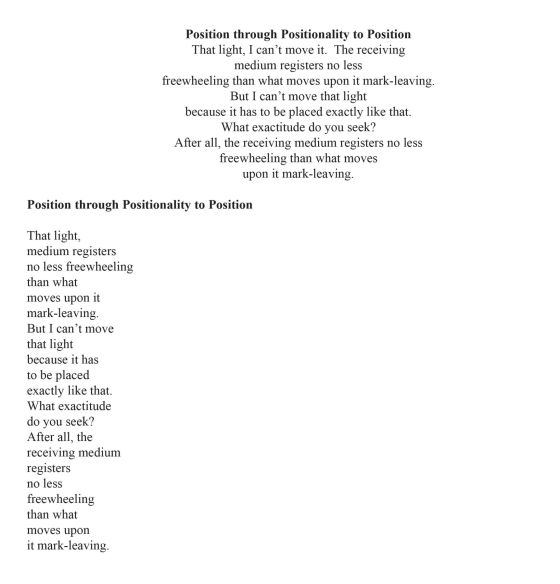

Arakawa, Name’s Birthday (a couple), 1967, oil on canvas

This investigation of light reaches its zenith in Arakawa’s installation Ubiquitous Site X (1987-91). Walking under the pink rubber drapery into a dark enclosed space may at first seem to be providing an experience devoid of light, and with the uneven terrain of the base of the structure, one would indeed need to focus in on other senses in order to be able to move around, and, in the process, one might become more aware of their own body in general. The heart beats and breath moves in and out of the dark inside of the body. Since this darkness is now all around you, does the sense of your personal boundary become more indefinite? Does it get pushed outward to find its limit at the external edges of the installation where you know the light was? If the light is not within, it must be without, or does it ring each person like a halo as Keller describes? With Keller’s influence, we find that light, the thing that is excluded, has perhaps become the most important point of focus in this particular setting. The lack of light allows you to engage the space on many levels. When we can see, we can observe limitations; when we can’t see these limits, the space becomes ubiquitous — without clear definition, you could in theory move your body however you want to, as long as you can overcome any trepidation. Gins tried to put her own thoughts on the matter in poem form and came up with two possibilities with which she was comfortable.

Excerpt from chapter 25 “Brave Light”, Helen Keller or Arakawa (1994)

Arakawa, Ubiquitous Site X, 1987-91

Many of the ideas discussed so far are featured prominently in the Reversible Destiny Lofts MITAKA – In Memory of Helen Keller (2005). Archetypal, diagrammatic forms are scaled up and repeated; along with multi-textured surfaces, this allows people to navigate the space using other senses. Tours are sometimes given blindfolded to underscore the fact that this architectural surround teaches you how to exist in the space even without the use of sight, in a matter similar to Ubiquitous Site X (1987-91).

Interior view of Reversible Destiny Lofts MITAKA – In Memory of Helen Keller (2005)

Interior view of sphere room inside Reversible Destiny Lofts MITAKA – In Memory of Helen Keller (2005)

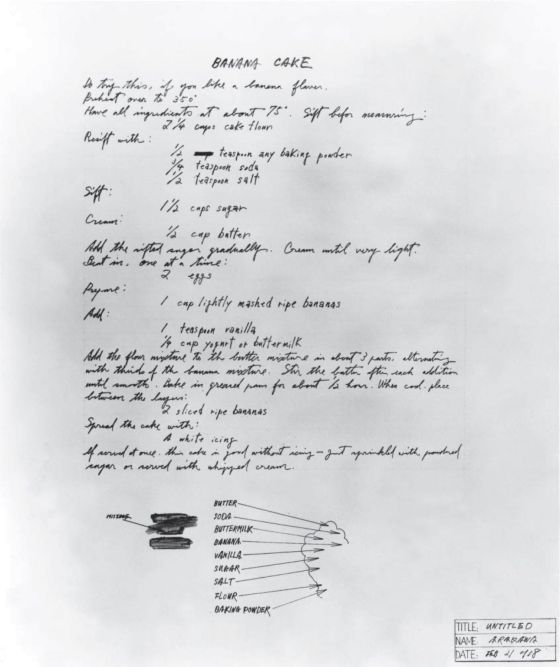

This brief exploration of Helen Keller or Arakawa (1994) has offered a mere taste of what can be found in Gins’s mellifluous prose, which is worth savoring in its full complexity. We have gone from ekphrasis, to the concept of architectural body, to spacetime, to the experience of light within that spacetime. Let’s end on a more lighthearted note with the invocation of a sense thus far ignored – taste. In the book, Gins juxtaposes Keller’s dream of a long string of peeled bananas hanging in her dining room, bunched in such a way that she could easily eat her fill, alongside Arakawa’s painting of a recipe for Banana Cake, Untitled (Banana Cake), 1968. In both instances, boundaries are at play. For Keller, the removal of the peel makes the fruit more accessible and she is able to enjoy them immediately. In Arakawa’s work, the viewer is presented with a boundary they must overcome – the cake is not yet made and gratification is therefore delayed. In this recipe painting, we again see separate objects that come together to form one unique thing, but we can imagine the taste of each separate ingredient, some with more pleasure than others, before imagining the texture and taste of the ingredients coalescing in cake form. As Gins indicates, the banana adds moisture and volume to the cake in addition to its familiar sweet flavor, and in this cake form, the many seeds within a banana are suddenly diffuse and visible. We can only do this, though, if we have had banana cake before. It would be very difficult to simply imagine what the combination of a set of ingredients would taste like and what texture they would have when mixed and baked together had we no previous experience of it, something Gins refers to as the “report of the thinking field in action.” And so, she concludes, why not “[p]ropose a recipe rather than a theory. Another thing to consider is how much preferable it would be to end up with a banana cake than with a weak and misleading metaphysics.”

Arakawa, Untitled (Banana Cake), 1968

Sources:

Gins, Madeline. Helen Keller or Arakawa. New York and Santa Fe: Burning Books, 1994.

Gins, Madeline. Heren Kerā matawa Arakawa Shūsaku (Helen Keller or Arakawa). Translated by Momoko Watanabe. Tokyo: Shinshokan, 2010.