Dear Friends,

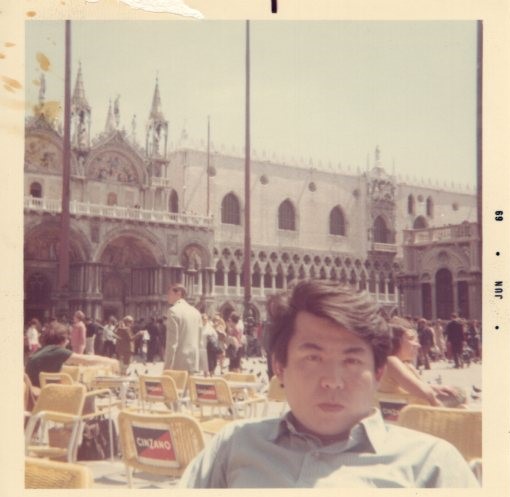

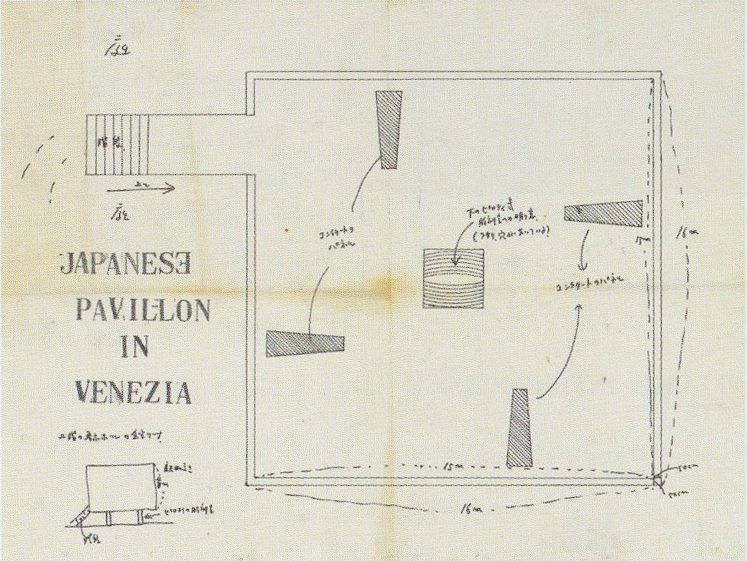

For Ambiguous Zones 9, we travel to the Japan Pavilion at the 35th Venice Biennale that took place in 1970. Marking the first time the inner gallery was reserved for a single artist, art critic Yoshiaki Tono, the commissioner of the Japan Pavilion, chose Arakawa for that year. Several canvases were exhibited from Arakawa’s large-scale project, The Mechanism of Meaning, which began in 1963 and was still in progress at the time. Developed alongside Madeline Gins, this series of panels rigorously interrogated perception, the process of receiving, organizing, and interpreting information using our senses, in this case mainly sight. These works were accompanied by related drawings and diagrammatic paintings from the 1960s that turned the show into a retrospective of Arakawa’s work over the previous decade.

Yours in the reversible destiny mode,

Reversible Destiny Foundation and the ARAKAWA+GINS Tokyo Office

The 35th Venice Biennale took place in 1970 in the shadow of the student protests of 1968. To address what Yoshiaki Tono, the commissioner for the Japan Pavilion in 1970, saw as problematic with the exhibition’s national framework, he decided to choose an artist, Arakawa, who reflected what he felt could be a common theme for the Biennale as a whole—the practice of conceptual art.[1] This was the first time that the inner gallery of the Japan Pavilion had been dedicated to a singular artist, though a sculpture by Mono-ha artist Nobuo Sekine was included outside.

The focus of the show was several large panels from The Mechanism of Meaning, a project that was still in progress, began in 1963 with Arakawa’s partner, Madeline Gins. This was the first time that The Mechanism of Meaning was shown, with Arakawa and Gins completing the project for its first publication in 1971.

Drawings and canvases from the 1960s rounded out the gallery, creating a retrospective of Arakawa’s work from that decade. Like The Mechanism of Meaning, these works explored the process of meaning-making through language, and the different stages of (mainly visual) perception—stimulation, observation, interpretation—occurring at both the preconscious and conscious levels.

The Biennale catalogue entry was written by Greek-American poet and art critic Nicolas Calas, who used the allotted space to explore in brief Arakawa’s use of signs in a strange context to make the viewer question what their next “visual move” should be.[2] Calas suggested that offering simple instructions when the “visual structure of the reference is unexpected” served to widen the rift “between what you see and what you know.”[3]

In an article for the New York Times, Frederic Tuten discussed the boycott of the American Pavilion by “more than half of the 47 American artists”, who withdrew their works “in protest against the war in Vietnam and Cambodia.”[4] Naming Richard Smith and Arakawa as the only two artists pursuing more traditional art “worth discussing,” he goes on to offer these considerations of Arakawa’s work:

Arakawa’s series of 13 paintings bear images and text—words and sentences posed as instructions to the viewer—which if taken literally would blur or modify the viewer’s reading of the images and which also serve as visual structures in the painting. The work seems superficially formal and frigid but it decidedly carries great reserves of intelligence and personality.[5]

As at the 34th Biennale in 1968, where artists protested war, unfair working conditions, and uneven power structures in part by removing their works from display by turning them to face the wall or covering them up, American artists also made a political statement at the 35th Biennale by pulling their work altogether. The power of the artist is distilled into this simple act of withholding work so that it cannot be seen, making both its display and lack of display a political act as well as a social one. Arakawa’s work may not seem overly political at first glance, but in the context of the 35th Venice Biennale, following the upheaval of the 34th, it becomes evident that Arakawa and Gins’s exploration of visual perception, as well as the very act itself, straddles both the political and social realms.

We hope you enjoy these photographs of Arakawa’s work at the Japan Pavilion at the 35th Venice Biennale!

[1] Ignacio Adriasola, “Japan’s Venice: The Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale and the ‘Pseudo-Objectivity’ of the International,” Archives of Asian Art 67, no. 2 (2017): 223.

[2] Nicolas Calas, “Shusaku Arakawa,” in 35. Biennale internazionale d’arte: 24 giugno-25 ottobre 1970 (Venezia: La Biennale di Venezia, 1970), 46.

[3] Ibid., 47.

[4] Frederic Tuten, “Soggy Day in Venice Town,” New York Times, July 12, 1970, sec. Archives. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/07/12/archives/soggy-day-in-venice-town-soggy-day-in-venice.html.

[5] Ibid.